Building, Exploring, Composing

“Building an Instrument Is Composing” was the title of our most recent lab, a reversal of Helmut Lachenmann’s famous “composing is building an instrument.”

We were happy to welcome two Dutch guests that happened to be visiting Copenhagen for the NIME (New Interfaces for Musical Expression) conference. 1

Marije Baalman is an artist based in Amsterdam with a wide background ranging from an early interest in music, theatre, and writing short stories, to studies in applied physics, acoustics, and electronic music. This palette of interests is reflected in activities ranging from (live-)coding and working with wireless sensors, to installations and performance:

“To fly a kite is playing an instrument, where subtle gestures with the hands can have profound changes in the direction that a kite is flying.” Marije’s wind instrument transforms a kite into a true wind instrument through the use of various sensors whose sonified data is made audible through loudspeakers in a backpack worn by the flyer/performer. Chrysalis, a performance piece involving sound, lighting, and a specially built fabric cocoon makes slow movements audible through the use of sensors.

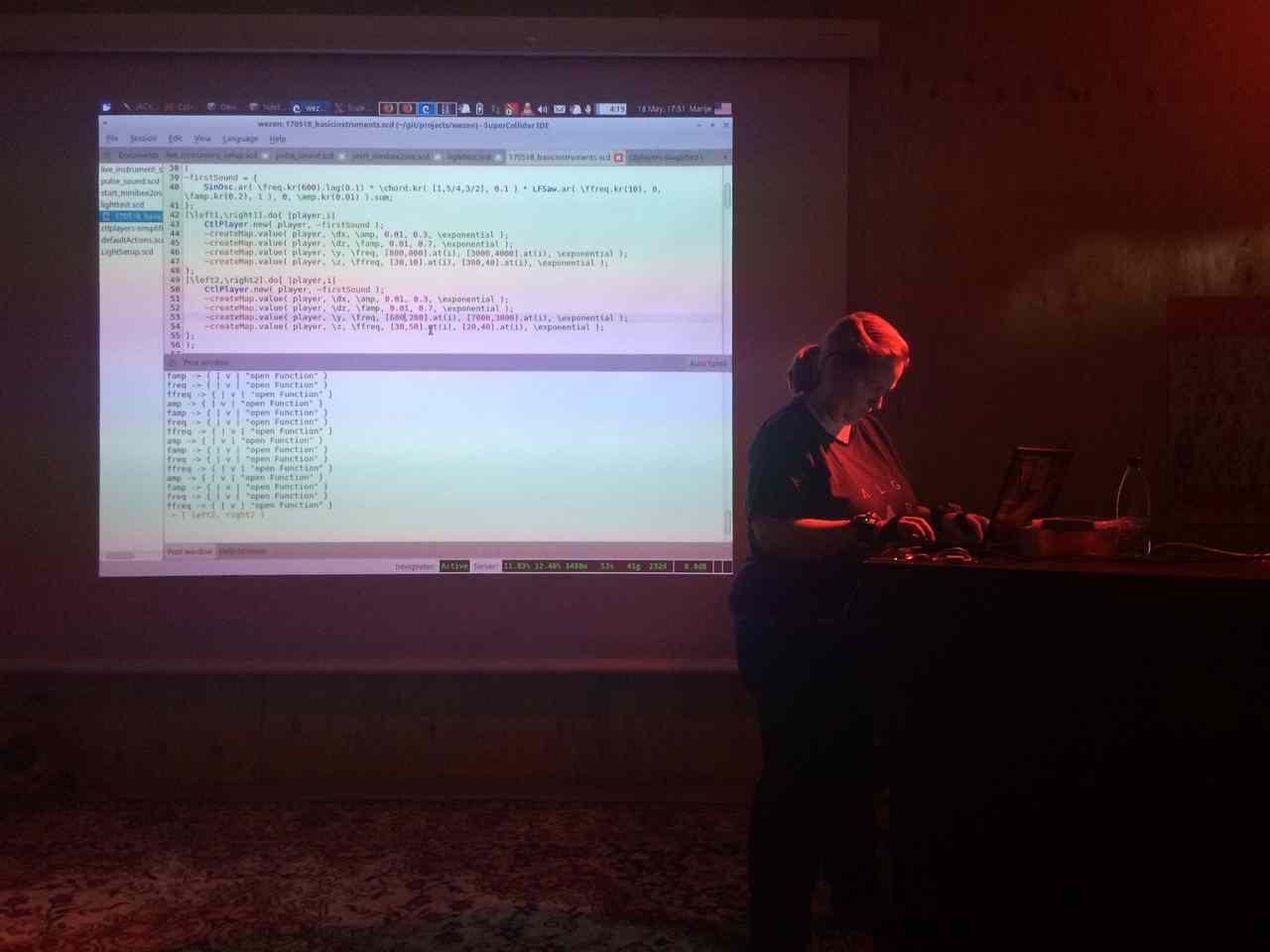

In the lab she also gave a live demonstration of Wezen-Gewording (Becoming) a piece that aims to bring the process of making a piece to the stage, with data recorded from wireless sensors attached to her hands recorded live and then transformed though live-coding.

* * *

Dianne Verdonk started out playing the cello and double bass, but from an early age got interested in extending them with electronics. Given the nature of the instruments, especially the size of the double bass, she was acutely aware of the correlation between movement and changes in sound on the one hand, as well as the sometimes awkward body positions that can result. Her frustrations with the lack of correspondence between turning a knob on an electronic instrument and the potentially large changes in sound that can result, led her to creating her own instruments.

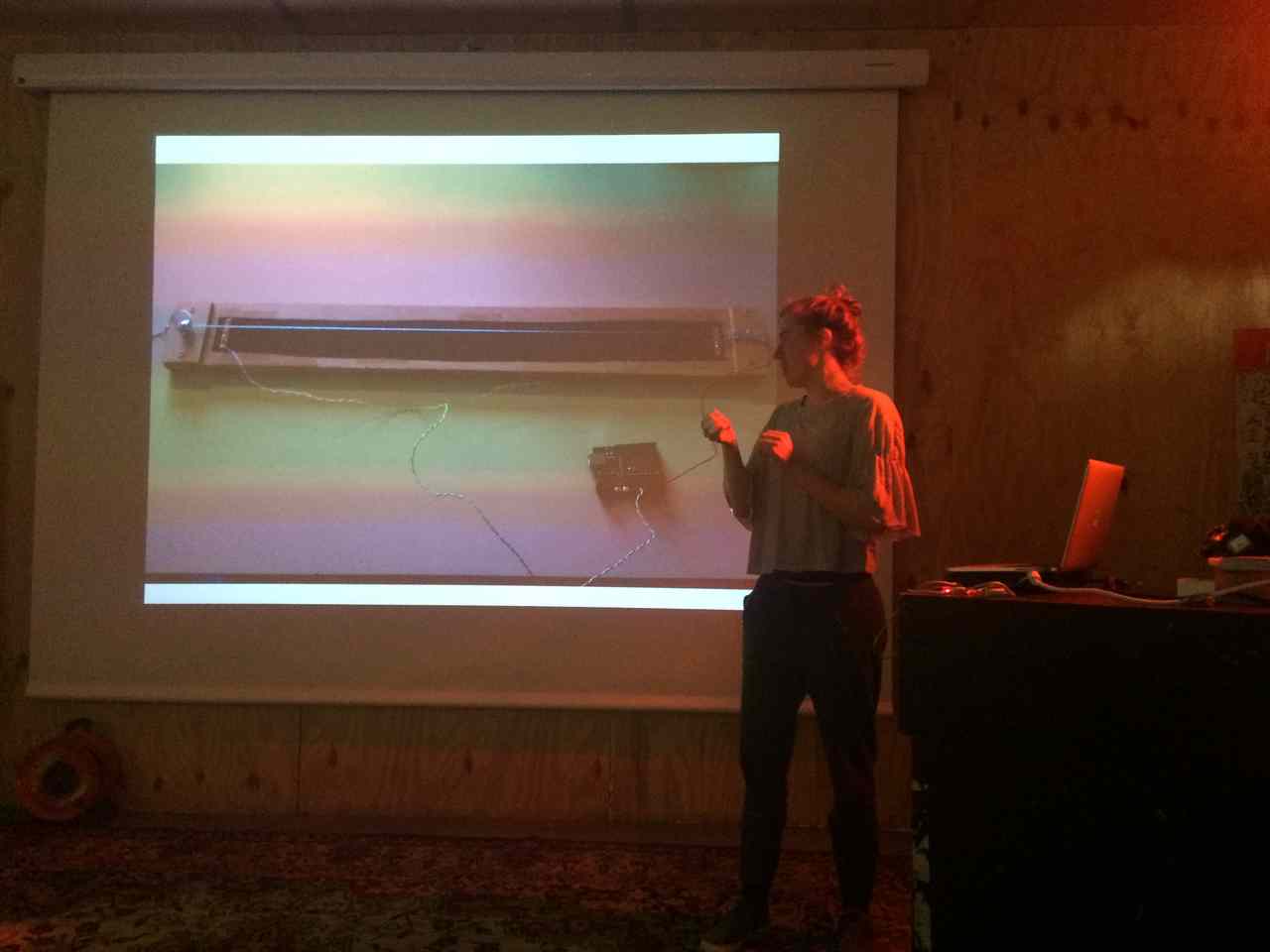

La Diantenne extends the basic idea of a string with circuitry and an Arduino, and attempts make clear the relation between what the performer is doing and the sound that results.

Rather than extending a physical instrument with electronics, the Bellyhorn takes the warm round sound a Moog Slim Phatty as it’s starting point and imagines a physical container to match it – one that involves working your body around it in both intense and relaxing ways.

The pitch of the underlying drone is altered by lifting the mouth of horn. A microphone in the mouth of the Bellyhorn feeds the Slim Phatty with pitches creating low difference tones. (Upper frequencies are cut off by a low pass filter.) The sounds are passed to a studio monitor (cone pointing up) placed in a flight case (which also acts as a resonator) which is covered by cushions and a leather cover giving the Bellyhorn’s its distinctive shape.

Dianne provides detailed descriptions, sketches and videos on her site for what turned out to be a somewhat social instrument (also suitable for children), both in it’s construction (a collaboration with fabric and interface designers) and use.

* * *

Ida Raselli, an artist currently studying at the Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen, works with sculpture, often in the form of oddly working machines.

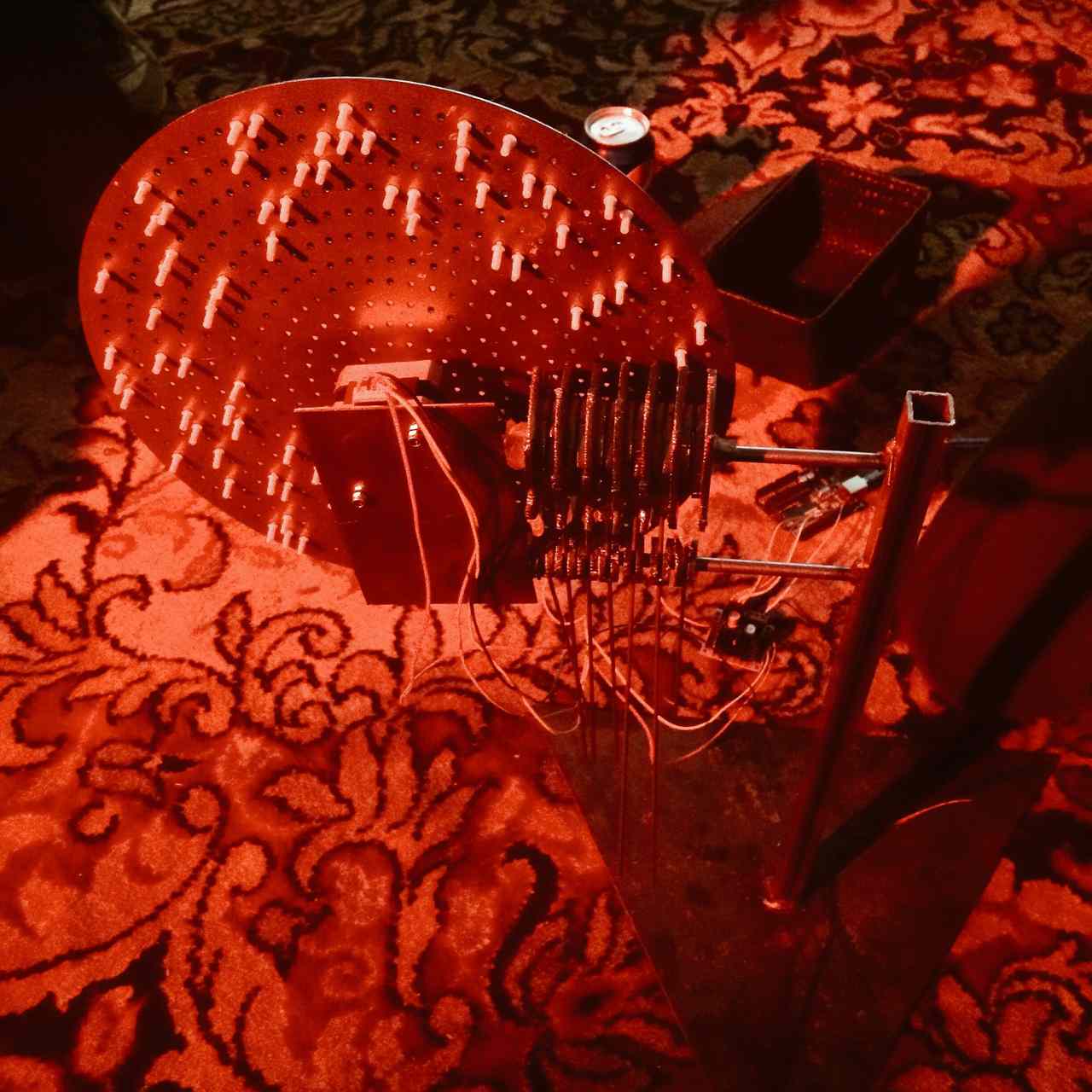

She demonstrated a work in progress inspired by Polyphons – old music boxes from before the age of the gramophone in which holes punched in a large circular metallic plate trigger sounds. She was inspired by the mechanical aspects of the device, protrusions triggering gears that trigger a comb, as well as the way in which a drawing or mapping could be given sound: The visual aspect of the disc that doubles as a kind of punch card – a form of programmable communication.

Her motivation for building these ‘contraptions’ has largely to do with turning machines inside-out in order to give access to how they work: Since technology has become so pervasive in our lives and is deeply shaping our behaviour and the way our brains work, it should be investigated. Current technology seems magical, but we aren’t in control and don’t get to see how it works, despite our dependence on it.

While old Polyphons were cranked by hand, the work she presented is driven by a motor that spins depending on the strength of surrounding human generated frequencies – those from WiFi and cellular phones, for example. It is an attempt to make visible the invisible communication that surrounds us constantly. The waves that hold our dreams and desires (and love), and bind us together.

Ida explained that creating a work such as this was for her largely a matter of agency. A process of challenging power structures. A challenge for herself to come to grips both with making the intricate parts for the instrument and learning to program the Arduino picking up the radio waves – a departure from the water and clay that she is most comfortable with.

* * *

Alex Mørch is a Danish composer and artist whose creaky home-made ‘music-aggregates’ add a visual and poetic dimension to concerts in which he combines mechanical, electronic, and acoustic elements in an often spatial and narrative concert-form.

For Frankenstein’s Lab he presented a small robot that he had used in a performance and explained his preference for the unpredicatable, glitchy character of his self-made robots rather than the polish of industrial robots that could potentially also be put to artistic purposes.

This particular robot generates sounds both through it’s mechanics, as well as small speakers that basically amplify its circuitry. In other pieces his robots are combined not only with performers, but also classical instrumentalists. His quirky constructions seem more like living things and lend themselves well to being presented together with human performers. The strange effect of the robot somehow seeming alive with all it’s spasms and unpredictability was particularly pronounced seeing it in front of us in real-life – an aspect that interestingly almost completely dissappears when seeing it on video.

* * *

After the presentations I asked each of the presenters for their thoughts on the relation between making/building things and composing for them, and the possible tension between those aspects. As the theme for the day suggested, composing seemed to have been subsumed into the process of building instruments – that one then improvised with.

For Marije the nature of code means that it is never fixed. Performance deadlines drive the development of a piece and provide intermediary moments of focus and stability before moving on to the next stage.

For Dianne composing and building are different. Building is more tangible – an activity in which one keeps on iterating. With a new instrument improvising is naturally the first thing one does – it’s a way of exploring the instrument.

Does one compose for an instrument like the Bellyhorn, or improvise with it? Dianne resorted to recording improvisations, notating them, and then placing the resulting sheet music in the mouth of the horn as a guide for performances. However, the notations aren’t yet a good translation, she finds. She prefers to think in intervals and finds it more convenient to write numbers referring to the intervals to be sung against the drone pitch. She sees it as a process of trying things out and reflecting on them at the same time. A process of preparation as well as analysis.

Alex told of how important he found the process of slowly getting to know the characteristics of the robot as he built and programmed it. Even when welding he found himself thinking of the sound – the subconscious doing a whole lot of processing during the building stage. This meant that once he finally got round to composing for his machines, the writing went relatively quickly.

He also pointed out that since many of his constructions only last for a single performance, it made sense that the focus wasn’t on composing “eternal masterpieces” for them.

Special thanks to Lars Kynde for helping put together this edition of Frankenstein’s Lab, and Katrine Gregersen Dal for taking care of all the practicalities and providing tasty tapas!

-

← A Tryout, a Travelogue, and an Inimitable Orchestra

This lab report is very much overdue – It’s been over a …

-

Frankenstein’s Lab, following the initiative of …