Frankenstein’s Lab at Illutron

28th of April 2015

Sandra Boss, Harald Viuff, Christian Liljedahl and Tobias Lukassen each presented at Frankenstein’s Illutron Lab.

Christian started out by giving us a tour of the barge and told about the many projects that have been initiated by Illutron through the years, to which the many thingys and half technological contraptions that are to be found in every nook and cranny testify. He made an important call which was later repeated: If you have ideas and can use the place, group, or facilities for something or other – feel free to come and join in!

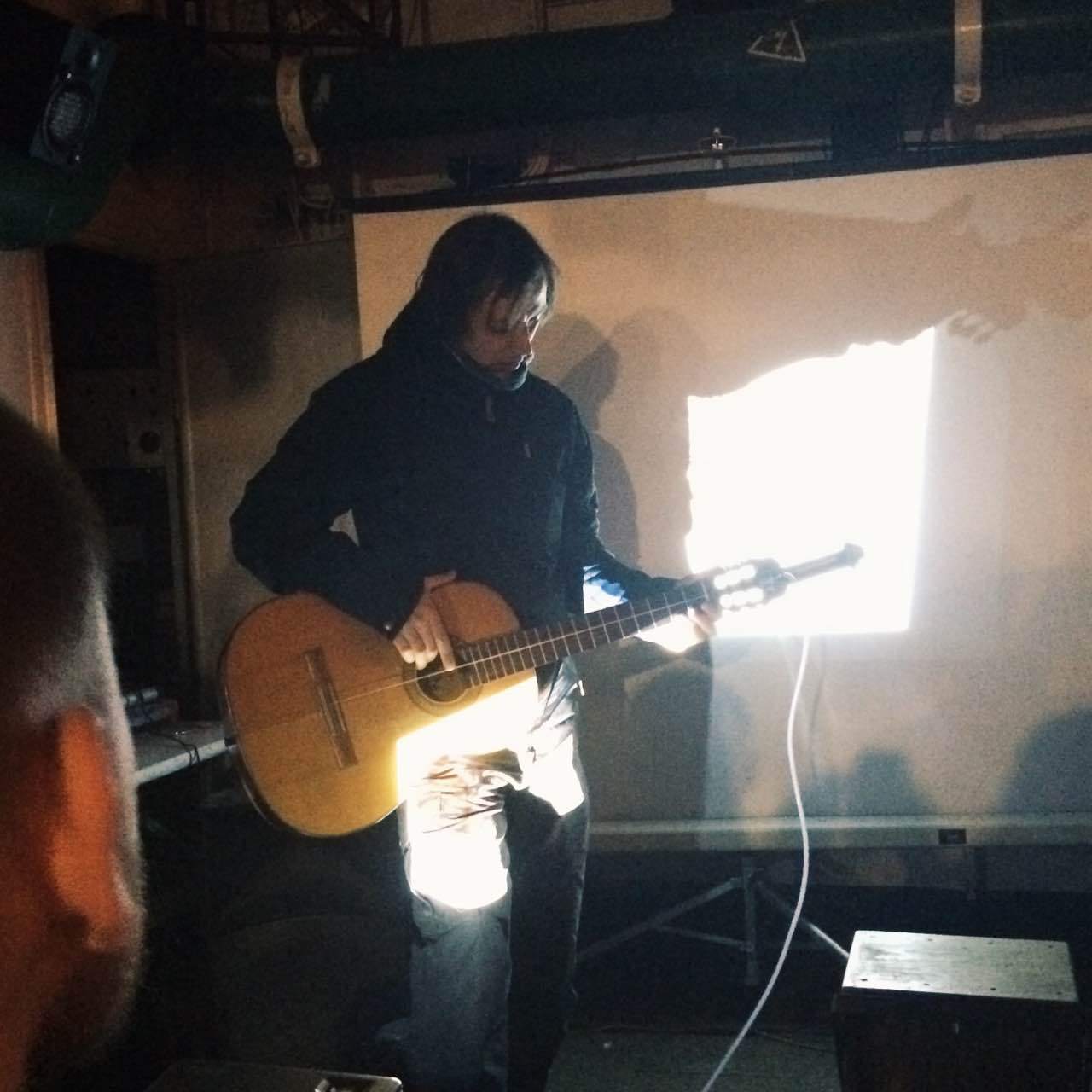

The first presentation was by Sandra Boss who played a composition on and for her MIDI-controlled organ before she telling a little about her aesthetics and thoughts concerning the relationship between music and instrument. Christian and Tobias were the evening’s closing presentation and presented both their experiments with pneumatically tensioned strings as well as a video documentation of a doomsday missile trombone. We didn’t have any problems with not to hearing the latter live since Christian explained that the sound was so powerful that it had hurt his ears even though he was wearing both earplugs and external hearing protection.

Both Sandra and Christian take their point of departure in the by-products of instruments and machines which were actually created with a different purpose in mind. However, their relationship with sound seems to move in the opposite directions in relation to their respective starting points. Sandra’s point of departure is media created with the complete control of sound in mind. Her presentation was based on a specially built organ, but she has also worked with other sound-generating media, such as tape recorders and tone generators. What interests her is however not the media’s original function but rather the additional sounds which are the result of their imperfections. With the small organ she brought along she presented a composition that made full use of the instrument’s imperfections and additional sounds such as the organ’s air sounds, the differences between the pipes and the instrument’s unstable reaction to changing air pressure.

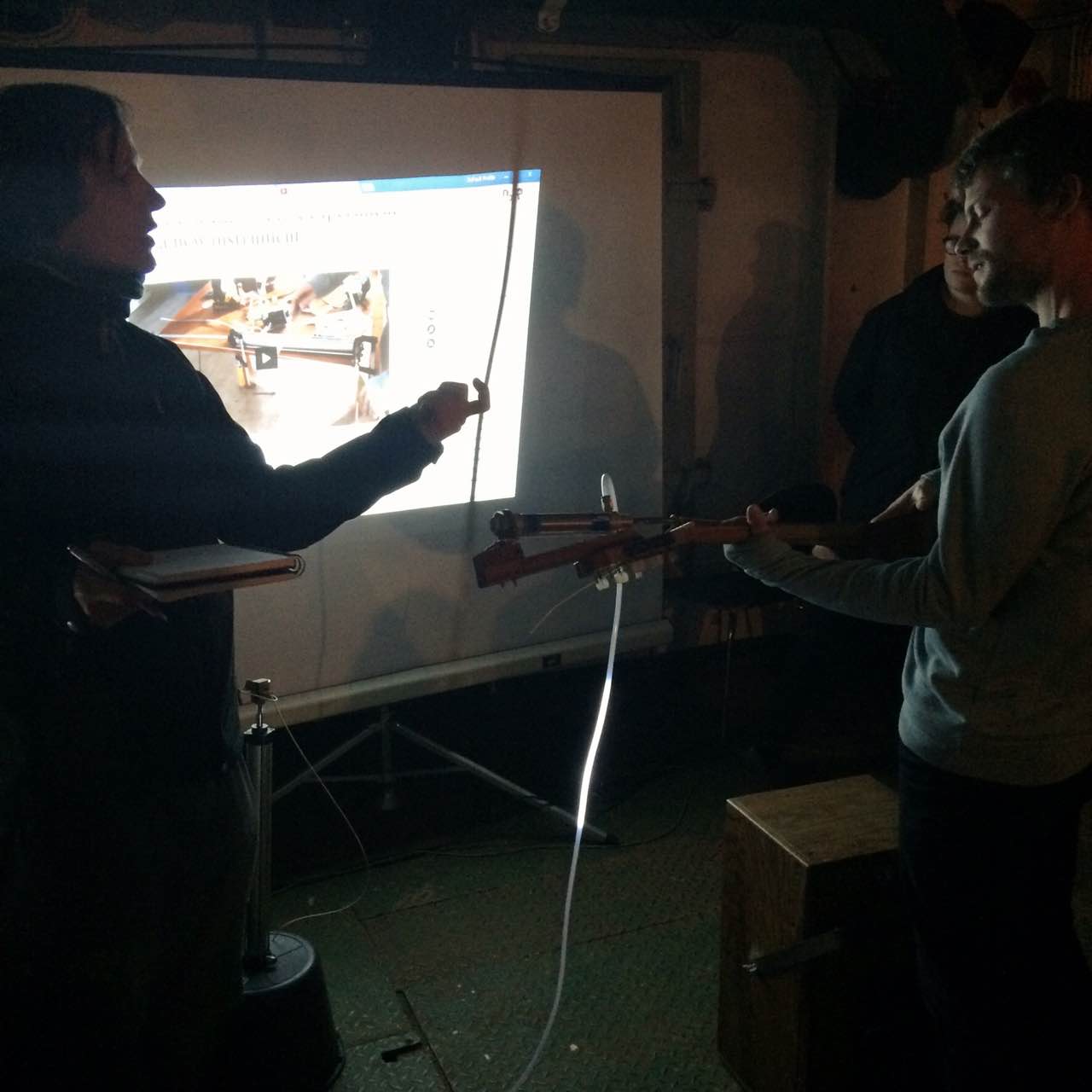

Christian and Tobias, in contrast, took their starting point in machines and technologies that were not originally intended for a musical function. They showed how the noise from a rocket fuel unit can be controlled with a retractable pipe system, somewhat like a trombone. From a functional point of view the rocket noise may be said to be an unwanted byproduct, but like Sandra’s interest in the organ’s additional sounds, here these byproducts also become the main point of focus. In some cases, by-products may be so undesirable that our selective perception completely overlooks them, but it was uplifting to be reminded that a by-product can nonetheless be a rich starting point for creation, since it has long lain pure and untouched. It can be difficult to immediately see the musical potential of a noisy engine, but Christian and Tobias opened up the dream that that sound might be refined and placed in a context where both the engine and its noise can become a means of expression as rich and meaningful as more classical music instruments.

Harald let us hear sounds through his AmbiUnix speaker system. Unlike the other presentations the sound generators (the loudspeakers) were used precisely for the purpose for which they were created – a finely calibrated tool for precise audio production. The loudspeakers were placed in the form of a dome and the guests were invited to stand under and in-between the loudspeakers in order to follow the movements of the sounds. The system was possibly not as well calibrated as it could be and we were also perhaps a few guests too many to really be able to walk around and explore the sonic phenomena. But one could nevertheless imagine the potential of the system.

A physicist amongst the audience asked about the potential of precisely calculating different acoustic phenomena but Harald demonstrated a more direct relation to the movement of the sounds. He rather wished to offer musicians parameters as ‘direction’, ‘speed’ and ‘position’ that they can make music with just as intuitively as the sounds on their instruments. He urged, however, that one came and used the setup as one pleased, and should one be an acoustician or if you are inclined to making precise calculations it is a golden opportunity to experiment with the spatiality of sound. The setup is permanently in place at Illutron and all are invited to use it as they find interesting.

This openness is part of Illutron’s charm. Christian also finished off with an invitation to further cooperation, and let us know that he wasn’t expecting to patent his inventions.

This was the first Frankenstein’s Lab excursion to an artist community. This time round it was Illutron. I’m looking forward to the next trip to a new location.

This edition of Frankenstein’s Lab, guest curated by Lars Kynde, was the first in a series visits to other communities and locations. Sign up for our newsletter if you’d like to be notified about our regular labs and occasional excursions.

-

← Frankenstein’s Lab in the Dome of Visions

Frankenstein’s Lab in the Buckminster Fuller inspired …

-

‘Why on earth are so many young composers throwing …