Virtuoso

Anders Monrad has created Virtuoso, an iPhone app soon to be released on the App Store. We got together on Skype for an interview in which I asked him about his motivations for creating the app, his background as an artist, and the cultural and technical hurdles along the long path to creating it.

R.M: Anders, I’d like to ask you a few questions about the app you’re about to release on the App Store. It’s an app called Virtuoso and it’s going to be released on the 1st of November. And my first question is: What is it? Is it a game or is it an instrument or is it a work of art?

A.M: It has aspects of all three things. Basically I insist that this app is a piece of art, but I’m using inspirations from my previous work with computer games and more regular iPhone and iPad apps. I have created several app-prototypes – most of them experiments in treating my device as a musical instrument. I would call Virtuoso my first “mature” app – it is more of an integrated art-piece combining a visual part, a sound part and an interaction part. It is obvious, when you’re creating interactive art-pieces, that the interaction design is a very important, integrated part of the overall aesthetic of the piece. Virtuoso is based on gestural input from the user.

My intention with the app was to motivate the user to make a lot of gestures – actually a kind of dance with the iPhone – but without really noticing it. I was thinking of ways to refer to music tradition in general, especially the physical, symbiotic interaction between musician and instrument. But also, I wanted to refer to the social aspect of music tradition – I wanted to create an app that was interesting, not only for the user, but also for the spectators watching the user “dancing” with the app. Part of the inspiration for this aspect of the app also came from my friends in the computer game industry working with physical computer games…

R.M: It seem’s to blur the line between composing and playing an instrument a little bit because in a way it is a kind of instrument but by playing the instrument you can’t help but compose it seems, you end up with a little composition after having performed with it, if I understand correctly.

A.M: First of all, I wanted the app to be as easy to use as possible – so that whatever you did, something came out of it. I’ve been happy to see how my 4 year old son has had a lot of fun playing with it… On first sight it might seem like a toy making funny sounds – but after playing with it for a while, you will notice that there are also a lot of hidden structures involved, and that you generate a 15 second composition which is played back when you stop playing with it. When you listen to several such playbacks you will also notice that your interaction affects the composition. So yes – it is indeed somewhere between an instrument and a composition…

R.M: It was commissioned by an artists collective called Haandholdt (or Hand Held in English).

A.M: Haandholdt are an artist’s group consisting of visual artists. Their intention has been to put focus on digital devices as a new artistic platform. A platform which I consider somewhat of a revolution for the present day artist, in that it enables artists to promote and distribute art-pieces via the App Store directly to the public all over the world. In this way artists are no longer dependent on the traditional art institutions, with all of their heavy bureaucracies, nepotism, art-political considerations etc…

Different artists have developed apps for Haandholdt – mainly poets and visual artists. I’m the first musician to develop an app for them. And what makes me different from the others is, that I have developed everything by myself. The other artists simply came up with a concept and then left the actual development of the app to a programmer. It has been very important to me to do everything by myself. This is possibly because I have a background as a musician and a composer: I could never dream of coming up with a musical idea, and then ask someone else to realise it. In that way music is more inextricably linked to musical craftsmanship. In visual art, there is a stronger tradition of conceptual art where artists mainly come up with ideas and leave the execution to others. As a musician I have a certain pride, encouraging me to do everything by myself…

R.M: One could say that creating musical scores has got something that’s quite close to programming in the sense that it’s a set of instructions that then get carried out, either by a musician or a piece of technology, or by a computer. But what I’d like to ask a little bit more about is this path of learning how to program apps – because, as you’ve told us – it’s something you set out to do yourself instead of handing over that part of the process to other programmers – you’ve taken it upon yourself to learn how to program and do all the parts of creating this app, from the design to the concept to the actual programming itself. And from what you’ve told me before … that’s been quite a path. It hasn’t always been that easy to get your hands on the information and to find people that could guide you and help you along that path. One of the things I always find quite fantastic about the web is that you can see the source code for any web page you visit. You can use your browser to take a look at the source code and see how it was put together – but apps are a little more tricky when it comes to that because they’re sort of, packages that are quite polished, and then… it’s quite difficult to open up the hood and see what goes on underneath. So how have you… as a composer you’ve had visions, you’ve had ideas for what you could do with the medium of an app, but how have you gone about this process of tackling learning all the technical things you need in order to create it?

A.M: That was an act of will power – I’ve been really stubborn – for years, app-development has been something I really, really wanted to do – to get my hands on… But it’s also a very natural thing to me, to think in terms of systems and structures – to make programs, instructions, basically. I guess that’s also why I also became a composer in the first place. The fantastic thing about programming is that you can program everything, control everything. My previous history before getting into computer music was that I wanted to become a classical composer doing traditional music scores. But I was very frustrated with the lack of control I always felt with the final sounding product. I got terribly annoyed being dependent on musicians who seemed quite careless when it came to understanding and performing my music properly. So I soon lost my interest in collaborating with them. With programming, I have complete control on the whole process from start to finish. Curiously, before I studied composition at the Music Academy I was playing a lot of piano and was only composing music to be performed on the piano by myself. Looking back, that has always been my preferred way of composing music, staying in control of everything…

R.M: But now you’re nevertheless handing over control of the final result to the iPhone user downloading your app?

A.M: That seems like it a bit of a paradox, indeed… But what my app is about is not a fixed musical timeline, it’s rather a way of experiencing a certain kind of musical language or logic. It’s more like an improvisation tool, within a set of musical playing rules setup by me. Everything that happens within these rules is part of my design. But at the same time, it is also designed by the user. You could say that I’m not interested in the interaction with the intermediary musician, but in the direct interaction with the audience – in this case with the individual using my app…

R.M: I was thinking about something that you’ve mentioned repeatedly: about the app moving more into the sphere of art. How do you feel about the fact that the software platforms probably won’t exist in 5 years time – they’re changing so quickly. When it comes to a ‘to do’ app, that doesn’t really matter – in 5 years time we’ll have another ‘to do’ app and as long as it does its job it doesn’t really matter if it changes. But when it comes to something that’s a little closer to what we consider a work of art, how do you feel about that it’s somehow limited in time, despite all the hours and the effort that you’ve put into it? It’s not like a Beethoven piano sonata that can be played hundreds of years later – in 5 years time you might either have to reinvent it or update it in some way?

A.M: I think you could say the same about the classical electronic music. There has been a huge effort to update old setups from the 60s, 70s, 80s to fit new platforms, because they were originally composed for platforms that are now obsolete. What was it called… I think it was called Integra…

R.M: Yes. Integra live.

A.M: Maybe my project will become obsolete after a few years – but if its worth it, I might update it or someone else might – I don’t know… If this could someday become a classic piece of app-artwork that would be fantastic… But that’s not my main ambition. It’s almost a cliche to think of the modern composer as someone who talks about how his music is written for times to come – that it’s not being understood by contemporary audiences because it is “too much ahead of it’s time”… Rather than engaging myself in such clairvoyant activities, I prefer to focus on what is interesting here and now and to get immersed in the whole creative process involved. I focus on app-development, because that’s what I think is new and refreshing right now – in 5 years time it might be something else – then I can change my focus…

R.M: I’d like to come back to an earlier version of this app that you presented at Frankenstein’s Lab earlier this year, and what was interesting for me at that point was that there was far less of a visual aspect. You’d actually at that point decided to very much focus on the gestural aspects of the app and using gesture as a means of shaping and creating sound. And you wanted to avoid, as you told at the time, you wanted to avoid someone peering into a screen and getting lost in that activity and rather get people to move and use their ears. But it seems as if you’ve nevertheless built in a little bit more of a visual aspect over the last few months and so I thought I’d ask you about that. I know you also have a background as a visual artist and that visual things have also been important to you. Perhaps you could tell us a little about why it is you decided to include the visual aspect.

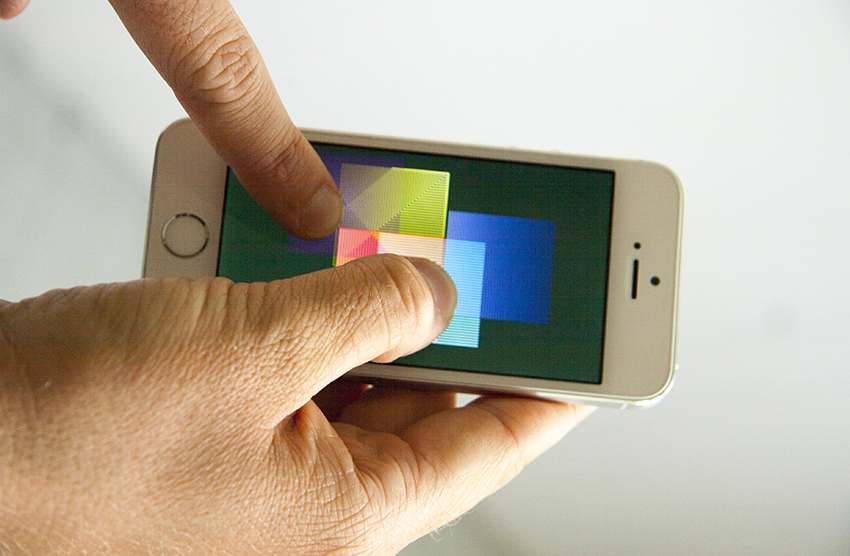

A.M: Eventually I found that it was necessary to provide some kind of interface showing the user when the 15-second composition playback was actually ending. Without that, the whole thing became a bit uncertain and unintuitive. People could think: ‘is it done now’? or ‘what is going on’?. The user interface I ended up designing is a very indirect one. Actually you’re not supposed to look at it while you’re moving the device around. And basically, what I wanted to avoid was that the user should get lost in the screen, because of my whole concept about the “dance-interface” and reference to social music making, with spectators watching the user acting as some kind of performer without noticing it… You’re not playing this app pushing buttons on the screen, instead you simply have to press one or multiple fingers onto the screen and then move it in different directions. Then, when you release your fingers from the screen and this 15 second composition is being played you have also generated a visual piece of art which also happens to be a visual interface – the user interface. So it has different functionalities… You’re not supposed to watch the screen until you’re passively experiencing what you have built up.

R.M: It’s quite interesting for me, this whole discussion that’s really come to the fore in the last few years with apps – the question of user interfaces and design, and design is often very focused on solving problems – in some ways, one might say that’s its definition, and art on the other hand is not so much a question of problem solving, at least not in the same way – and now this role of artist and designer is something that you’ve dealt with both aspects yourself . How’s that been… this pull between having to think about user interfaces and the way in which users interact with your app and use it, operate it, and at the same time the artistic element where it’s also an art work, that aspect of combining building an instrument and then the art that’s to be played on that instrument – rolling those two things into one – how have you found that? Is it mentally a tricky thing to move back and forth between the two sides or has it been a flow towards…?

A.M: I think you have to build a new mindset. There’s been an agenda, especially during the past 50 years or so, that art should be created out of a necessity – experiencing an art work should first of all not be easy – rather than being a pacifying pastime, art should encourage critical thinking and question the state of things… Within European classical music tradition, this philosophy has somehow resulted in endless repetitions of 60s avant-garde – I really don’t think anything new has happened in 40 or 50 years in the concert halls – and I always get bored to death when I go to new music concerts… Sometimes you have to change the medium in order to change the art form.

I think the concert hall is the reason why modern music composition has stagnated. Classical composers have to accept that society’s relation to music entered a new paradigm a long, long time ago with the invention of recorded sound and sound playback. It’s almost been 150 years!… The thing is, that the majority of people are not building their musical identity at concerts or concert halls anymore. At best, concerts might be considered as some sort of merchandise… In modern society, music consumers build their musical identity from listening to music in personal, individual spaces from sound recordings on iPods, CD-players etc. – or from using music apps on their personal devices. The concert hall comes after all of that – after you have built your musical identity. For some reason classical composers are stuck with the concert hall…

R.M: I find the ambition for this app quite fascinating, because on the one hand you’ve got this whole background of the avant-garde pioneers like Stockhausen and Nancarrow that are somehow in the backgroud informing some of your sound and aesthetic choices – and on the other hand you have this big drive towards making it completely accessible – as you said, you’re happy that your 4 year old son can pick it up and do something with it…

A.M: Yes, comprehensibility is very, very important to me. What I was also very frustrated with as a composer was, that I felt no one from outside the music world would ever take me seriously – no one takes modern composers seriously anymore, that’s my experience. On the other hand I have experienced a lot of people suddenly take my newly achieved programming skills very seriously – a typical reaction I get could be something like: “so you play music, hmmm – but you can actually program music also?! – wow, that is really something…”. If music was the acclaimed skill of the 19th century, then programming is the acclaimed skill of the 21st century. Programming is a new craft that is being taken seriously in society. So my advice to all musicians is that they should learn how to program – it should definitely also be a part of all music educations.

It’s so annoying being a musician who has developed an amazing musical craft and no one really cares about it. And also you have all these amazing artworks, musical artworks, which no one really appreciates – at least in the way they deserve. I think it’s such a shame that experimental music, especially avant-garde classical music, is just being considered as some kind of novelty by the general public, if not downright ridiculed! So it has been a very strong urge for me to make it accessible, even fun to approach. If I can create an abstract, avant-garde piece of music and have children have a good time playing with it, I have reached my goal. With Virtuoso, I think I have finally achieved something close to that. Of course I will develop even better apps in the years to come. But this is definitely a good, satisfying step in the right direction.

R.M: Right - and it’s going to be released on the 1st of November. It will be available on the App Store. And it’s only available for the iPhone, is that correct?

A.M: Yes, I experimented with the app on iPad also, but since you have to move the device around, holding up to 5 fingers on the screen at the same time, there was a risk that you would drop your iPad on the floor – It would need a completely different interaction design for the iPad. But it works very well with a small, handy device like an iPhone.

R.M: Yeah, it’s actually very beautiful to watch someone performing it. You presented it a Frankenstein’s Lab earlier this year and it was really nice to see the gestures and directly see how those gestures are being translated into sound.

On the 30th of October there is an opening in which the app will be presented and there will actually be a musical performance with percussionist Ying-Hsueh Chen, using it as an instrument. That’s at the Nikolai Kunsthal here in Copenhagen.

It’s going to be really interesting to see how this gets taken up. It’s a fascinating jump into the world of apps and design and art and bringing all these things together, and I hope you have a lot of success with it. I’m looking forward to experiencing the performance and trying it out myself.

Read more about the app on Anders Monrad’s website.

-

← Unusual Concerts In Alternative Spaces

The next lab, in which we explore the theme of creating …

-

Improvisation, Extended Techniques, an iPhone Sound-Sculpture and a New Location →

After a small break in our schedule …